How Brands Can Support Indigenous Communities on Social—the Right Way

There is a growing interest among businesses, large and small, to add their voices to the nationwide acknowledgment of the trauma inflicted upon Indigenous children at Canada’s Indian Residential Schools.

This was amplified in 2021 with the location of nearly a thousand unmarked graves at sites of the now-shuttered institutions—and we know thousands more have yet to be discovered.

On National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, it’s important for Indigenous people (and, frankly, for non-Indigenous people) to see businesses and brands honour those who lost their lives through the 165-year program of assimilation.

It’s also important for us as Indigenous people to see them pay tribute to those who survived their years at the notorious schools.

But deploying the hashtag #TruthAndReconciliation or #EveryChildMatters can be a risky undertaking. There are many ways to make a well-meaning blunder that will prompt eye rolls throughout Indigenous Canada or, worse, to accidentally post something that’s outright offensive.

That’s why I wrote this blog post. I’m a Métis woman and lawyer who has been the CEO of the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC), the largest organization representing Indigenous women in Canada, since 2017.

I, and other Indigenous women who follow social media, brace ourselves as September 30 rolls around, waiting for the inevitable ham-fisted attempt by non-Indigenous actors to be part of the commemoration.

Please don’t misunderstand. We want you to be there with us as we grieve and as we remember and as we honour. We just want you to do so respectfully. So here are some guidelines.

What is the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation? How is it different from Orange Shirt Day? And what should we call it on social media?

The National Day for Truth and Reconciliation was declared by the Canadian government in 2021, after the graves were found at Indian Residential Schools.

(Please note: “Indian Residential Schools” is the official name for the schools and a construct of the colonial mindset of 19th Century Canada. In any other context, the word Indian is extremely offensive when used to refer to the Indigenous people of Turtle Island.)

National Day for Truth and Reconciliation is a day for honouring the victims and celebrating the survivors of the schools. And it’s a federal statutory holiday, so it applies to all federally regulated workplaces. But it’s been left to provinces and territories to choose whether it is marked within their own jurisdictions.

We note that it took Canada’s federal Liberal government (which came to power in 2015 promising to act on all 94 Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission) nearly seven years to meet the relatively simple Call Number 80. It urged the creation of the holiday “to ensure that public commemoration of the history and legacy of residential schools remains a vital component of the reconciliation process.”

There is no doubt that the discovery of the graves—which the Truth and Reconciliation report said would be found if an effort was made to look for them—bolstered public support for such a day.

September 30 should be thought of as our Remembrance Day, and it should be referred to by its official name: the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. Any other name fails to communicate the sombreness of the occasion, just as it minimizes Remembrance Day to call it Poppy Day.

September 30 is also Orange Shirt Day, reminding us of the day in 1973 when six-year-old Phyllis Webstad from the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation arrived at the St. Joseph Mission Residential School, just outside Williams Lake, B.C.

She was wearing a vibrant orange shirt her grandmother bought her to match her excitement for her first day of school. But the shirt was immediately taken from her by school authorities and never returned—an event that marked the beginning of the year of atrocities and torment she experienced at the institution.

We wear orange shirts on September 30 as a reminder of the traumas inflicted by residential schools. If you’re specifically referring to Phyllis’ story on social media, then it is appropriate to call it Orange Shirt Day.

But the holiday is the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, and should be referred to as such.

What terms should you use when you refer to Indigenous people? (Terminology 101)

Speaking of terminology, when is it appropriate to refer to someone as First Nations, Métis, or Inuit, and when is it appropriate to refer to someone as Indigenous?

First up, here’s what those different terms actually mean:

- First Nations: The largest Indigenous group in Canada, these are members of the 634 First Nations spread across the country

- Métis: A distinct group of people who have an ancestral connection to a group of French Canadian traders and Indigenous women who settled in the Red River Valley of Manitoba and the Prairies

- Inuit: The Indigenous people of the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions

- Indigenous: The First Peoples of North America whose ancestors were here before the arrival of the Europeans

Next, where to use them: It’s always best to be as specific as you possibly can when describing us on social media.

Here’s a quick reference on the best way to refer to Indigenous individuals:

- Reference the person’s specific first nation and its location

- Reference the person’s nation and ethno-cultural group

- Reference their ethno-cultural group

- Refer to them as First Nations, Mètis, or Inuit

- Refer to the person as Indigenous

So, if someone is a Cree from the Cree First Nation of Waswanipi, say that. Second best would be to call them a Waswanipi Cree. Third best would be to call them a Cree. Fourth best would be to call them a First Nations member.

And fifth best would be to call them Indigenous, which is a catch-all phrase that includes all First Nations, Métis, and Inuit. But it also includes all Indigenous people around the world. The Māori of New Zealand are Indigenous.

Saying someone is Indigenous is like calling a Chinese person Asian. It’s true. But it misses a lot of detail.

If you don’t know how best to describe someone, ask us. Preferences vary from individual to individual.

But please, despite the fact that my organization is called the Native Women’s Association of Canada, which is a holdover from a much earlier time (NWAC was formed in 1974), please do not call Indigenous people ‘native.’

What role should brands play on social media on September 30?

At NWAC, our hashtag for the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation is #RememberHonourAct. We think those are good guidelines for everyone—individuals and businesses alike—on September 30 and, indeed, year-round.

Remember the survivors of the residential schools, honour them, and act to strengthen the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

If yours is a local business, pay tribute to the Indigenous people in your area. Acknowledge their traditional territory. Recognize that your operations are taking place on the land that they have shared with you, and that you and your employees are benefitting from that.

If you are a national brand, turn the spotlight back on the First Nations communities. Highlight the achievements and the contributions that First Nations people have made to Canadian prosperity.

Yes, September 30 is a sombre day of remembrance. But we don’t want pity. We want acknowledgments of past wrongs and promises that they will not be repeated, but we also want to embrace the promise of a better future in which Indigenous people can enjoy prosperous and happy lives free of historical trauma.

Are there other notable days for brands to keep in mind for Indigenous people?

Yes.

There are other sombre days.

Less than a week after the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, Indigenous women across Canada will gather at Sisters in Spirit Vigils to honour the women, girls, and gender-diverse people who have lost their lives in the ongoing genocide that targets us for violence. This is an annual event created to give support and comfort to the families and friends who have been left to mourn their loved ones.

On February 14, Valentine’s Day, annual Women’s Memorial Marches are held in cities and towns across Canada and the United States. They too are meant to honour Indigenous women and girls who have been murdered or who have gone missing.

And on May 5, we mark Red Dress Day, a day on which red dresses are hung in windows and in public spaces around Canada, again to honour the missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

But there are also joyous occasions.

Although there is not a specific date set aside, summer is the time for gathering. It is powwow season. Fall is the time that we traditionally rejoice in the bounty of the hunt.

On June 21, the Summer Solstice, we celebrate National Indigenous Peoples Day. This is a day for rejoicing in our heritage, our diverse cultures, and the contributions that Indigenous people are making to the complex fabric of Canadian life.

What social media mistakes do brands make on September 30?

The most egregious examples of brand behaviour around the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation are attempts to monetize our pain for financial gain.

If you own a clothing company, please don’t print a batch of orange shirts and sell them for profit. And don’t promote the sales of your shirts on social media. This happens every year and it is offensive in the extreme.

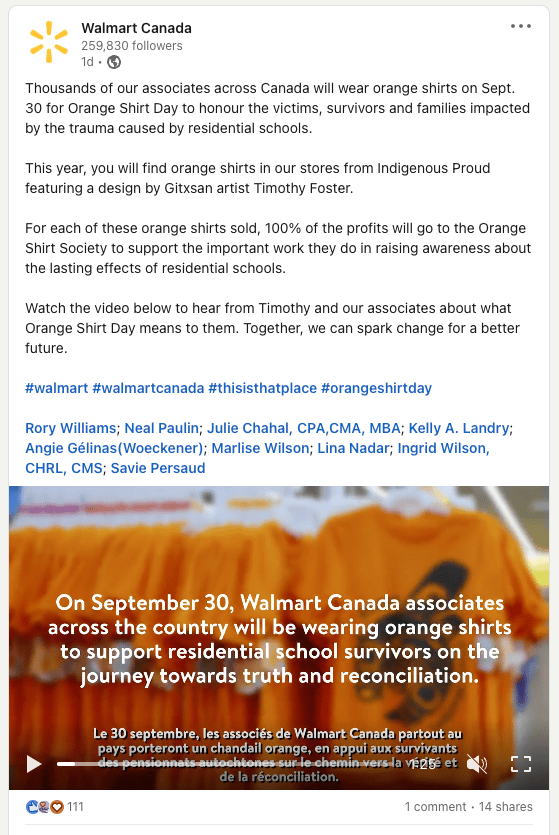

On the other hand, printing and selling orange shirts and then turning the profits over to Indigenous causes is a wonderful gesture of support.

And it’s not just the small brands that are doing this. Walmart, for instance, promises to donate 100% of the profits from its Every Child Matters t-shirts, which have been designed by an Indigenous artist, to the Orange Shirt Society.

Be the brand that does something like that.

In all of your social media posts, be mindful that this is our history. Every Indigenous person in Canada has been touched by the residential school experience, whether or not we or our ancestors attended one of the institutions. Be mindful of the traumas that can be brought to the fore with a thoughtless twist of words.

And again, Indigenous people are at a place where we don’t need or want pity. We need people to celebrate our accomplishments. We need to feel part of a society that is eager to include us.

What opportunities are there for intersections between Indigenous people and other social movements?

In a simple word: lots.

If there is a social justice issue being championed—whether that is Pride in the gender-diverse community, or climate justice, or prisoners’ rights, or racial equality—you’ll find Indigenous people at the forefront.

My organization is an example of that. We have whole units of staff working on all of those things.

Reach out to us, or other national Indigenous organizations (we list a few later on), to ask about ways you can get involved, projects you can promote, and causes you can stand behind.

This is a prime opportunity to collaborate with Indigenous creators who are passionate about the larger social issue at hand.

How can brands work with Indigenous content creators?

Find them and ask them. There are plenty out there. Any search engine will quickly turn up hundreds of names of Indigenous content creators and influencers, and many will be eager to collaborate with you.

Here are some examples of places to look:

- TikTok Accelerator for Indigenous Creators

- APTN Profile of Indigenous Creators

- PBS Article on Indigenous Creators

- TeenVogue Roundup of Indigenous Creators

- CBC Profile on Indigenous Creators

What Indigenous organizations can brands support or partner with?

Most of the National Indigenous Organizations are looking for partners. We, at NWAC, have terrific partnerships with brands like Sephora, Hootsuite, and TikTok.

@tiktokcanada Applications for the TikTok Accelerator for Indigenous Creators are now open! Indigenous creators, apply by September 15

But there are also smaller groups out there who would be delighted to hear from you.

One example that immediately springs to mind is Project Forest in Alberta which is working in partnership with Indigenous communities to restore sacred lands so that medicinal plants and native species will thrive again in First Nations communities.

There is also a range of organizations that are working tirelessly to improve the lives of the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit.

I would point to the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, Susan Aglukark’s Arctic Rose Foundation, The Martin Family Initiative, or the Indian Residential School Survivors Society.

Those are just a few. And of course, there is NWAC—we work tirelessly for the well-being of Indigenous women, girls, Two-Spirit and gender-diverse people.

What are some examples of brands that are supporting and/or highlighting Indigenous communities the right way?

Many brands are doing things right. I will again mention beauty company Sephora partnered with the NWAC to run a roundtable on Indigenous beauty to find out where they could improve. And they’ve acted on their learnings.

TikTok, likewise, has taken the time to reach out to us to ask for guidance on how to get engaged with Indigenous people and communities. And, over the past few years, we have worked closely with Hootsuite, providing advice and information.

But others are also making great strides.

I would point to the National Hockey League which has been unreservedly vocal in denouncing the racism directed at Indigenous hockey players. The Calgary Flames opened their season with a land acknowledgement.

Ahead of National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, the #Flames wore orange jerseys for the morning skate and the day will be recognized prior to puck drop tonight

pic.twitter.com/appz0sN7c9

— Calgary Flames (@NHLFlames) September 29, 2021

This would not have happened 10, or maybe even five, years ago. But society is changing, corporate behaviour is changing, the world is changing. And social media has had, and will have, much to do with that.

The post How Brands Can Support Indigenous Communities on Social—the Right Way appeared first on Social Media Marketing & Management Dashboard.

Related Posts

Categories

- 60% of the time… (1)

- A/B Testing (2)

- Ad placements (3)

- adops (4)

- adops vs sales (5)

- AdParlor 101 (43)

- adx (1)

- algorithm (1)

- Analysis (9)

- Apple (1)

- Audience (1)

- Augmented Reality (1)

- authenticity (1)

- Automation (1)

- Back to School (1)

- best practices (2)

- brand voice (1)

- branding (1)

- Build a Blog Community (12)

- Case Study (3)

- celebrate women (1)

- certification (1)

- Collections (1)

- Community (1)

- Conference News (1)

- conferences (1)

- content (1)

- content curation (1)

- content marketing (1)

- contests (1)

- Conversion Lift Test (1)

- Conversion testing (1)

- cost control (2)

- Creative (6)

- crisis (1)

- Curation (1)

- Custom Audience Targeting (4)

- Digital Advertising (2)

- Digital Marketing (6)

- DPA (1)

- Dynamic Ad Creative (1)

- dynamic product ads (1)

- E-Commerce (1)

- eCommerce (2)

- Ecosystem (1)

- email marketing (3)

- employee advocacy program (1)

- employee advocates (1)

- engineers (1)

- event marketing (1)

- event marketing strategy (1)

- events (1)

- Experiments (21)

- F8 (2)

- Facebook (64)

- Facebook Ad Split Testing (1)

- facebook ads (18)

- Facebook Ads How To (1)

- Facebook Advertising (30)

- Facebook Audience Network (1)

- Facebook Creative Platform Partners (1)

- facebook marketing (1)

- Facebook Marketing Partners (2)

- Facebook Optimizations (1)

- Facebook Posts (1)

- facebook stories (1)

- Facebook Updates (2)

- Facebook Video Ads (1)

- Facebook Watch (1)

- fbf (11)

- first impression takeover (5)

- fito (5)

- Fluent (1)

- Get Started With Wix Blog (1)

- Google (9)

- Google Ad Products (5)

- Google Analytics (1)

- Guest Post (1)

- Guides (32)

- Halloween (1)

- holiday marketing (1)

- Holiday Season Advertising (7)

- Holiday Shopping Season (4)

- Holiday Video Ads (1)

- holidays (4)

- Hootsuite How-To (3)

- Hootsuite Life (1)

- how to (5)

- How to get Instagram followers (1)

- How to get more Instagram followers (1)

- i don't understand a single thing he is or has been saying (1)

- if you need any proof that we're all just making it up (2)

- Incrementality (1)

- influencer marketing (1)

- Infographic (1)

- Instagram (39)

- Instagram Ads (11)

- Instagram advertising (8)

- Instagram best practices (1)

- Instagram followers (1)

- Instagram Partner (1)

- Instagram Stories (2)

- Instagram tips (1)

- Instagram Video Ads (2)

- invite (1)

- Landing Page (1)

- link shorteners (1)

- LinkedIn (22)

- LinkedIn Ads (2)

- LinkedIn Advertising (2)

- LinkedIn Stats (1)

- LinkedIn Targeting (5)

- Linkedin Usage (1)

- List (1)

- listening (2)

- Lists (3)

- Livestreaming (1)

- look no further than the new yorker store (2)

- lunch (1)

- Mac (1)

- macOS (1)

- Marketing to Millennials (2)

- mental health (1)

- metaverse (1)

- Mobile App Marketing (3)

- Monetizing Pinterest (2)

- Monetizing Social Media (2)

- Monthly Updates (10)

- Mothers Day (1)

- movies for social media managers (1)

- new releases (11)

- News (72)

- News & Events (13)

- no one knows what they're doing (2)

- OnlineShopping (2)

- or ari paparo (1)

- owly shortener (1)

- Paid Media (2)

- People-Based Marketing (3)

- performance marketing (5)

- Pinterest (34)

- Pinterest Ads (11)

- Pinterest Advertising (8)

- Pinterest how to (1)

- Pinterest Tag helper (5)

- Pinterest Targeting (6)

- platform health (1)

- Platform Updates (8)

- Press Release (2)

- product catalog (1)

- Productivity (10)

- Programmatic (3)

- quick work (1)

- Reddit (3)

- Reporting (1)

- Resources (34)

- ROI (1)

- rules (1)

- Seamless shopping (1)

- share of voice (1)

- Shoppable ads (4)

- Skills (28)

- SMB (1)

- SnapChat (28)

- SnapChat Ads (8)

- SnapChat Advertising (5)

- Social (169)

- social ads (1)

- Social Advertising (14)

- social customer service (1)

- Social Fresh Tips (1)

- Social Media (5)

- social media automation (1)

- social media content calendar (1)

- social media for events (1)

- social media management (2)

- Social Media Marketing (49)

- social media monitoring (1)

- Social Media News (4)

- social media statistics (1)

- social media tracking in google analytics (1)

- social media tutorial (2)

- Social Toolkit Podcast (1)

- Social Video (5)

- stories (1)

- Strategy (601)

- terms (1)

- Testing (2)

- there are times ive found myself talking to ari and even though none of the words he is using are new to me (1)

- they've done studies (1)

- this is also true of anytime i have to talk to developers (1)

- tiktok (8)

- tools (1)

- Topics & Trends (3)

- Trend (12)

- Twitter (15)

- Twitter Ads (5)

- Twitter Advertising (4)

- Uncategorised (9)

- Uncategorized (13)

- url shortener (1)

- url shorteners (1)

- vendor (2)

- video (10)

- Video Ads (7)

- Video Advertising (8)

- virtual conference (1)

- we're all just throwing mountains of shit at the wall and hoping the parts that stick don't smell too bad (2)

- web3 (1)

- where you can buy a baby onesie of a dog asking god for his testicles on it (2)

- yes i understand VAST and VPAID (1)

- yes that's the extent of the things i understand (1)

- YouTube (13)

- YouTube Ads (4)

- YouTube Advertising (9)

- YouTube Video Advertising (5)